Over the last month, I’ve been working with my friend Jack Schenkman to develop a model for a basic grid system made up of entirely intermittent generators. Our goal was to understand how the relationship between the average intermittence of renewable generators and colocated energy storage affected the overall system resilience and cost of electricity on a grid system with only renewable generation. We did this by first building a system with no energy storage, simulating the resilience and cost as a factor of the average intermittence of generators. We then colocated energy storage of varying capacity with each generator to see to what degree it could improve resilience and cost demonstrate the diminishing returns of excess storage capacity.

We were proud to show that our models were consistent with intuition. We showed how resiliency diminished linearly as the average intermittence of generators increased and costs increased as more expensive generators were utilized.

We then showed how adding energy storage improved the system’s resilience up to a degree, but the contributions diminished when the size of batteries approached the generator’s capacity. At this point, the only way to improve the overall system resilience was to add more generators.

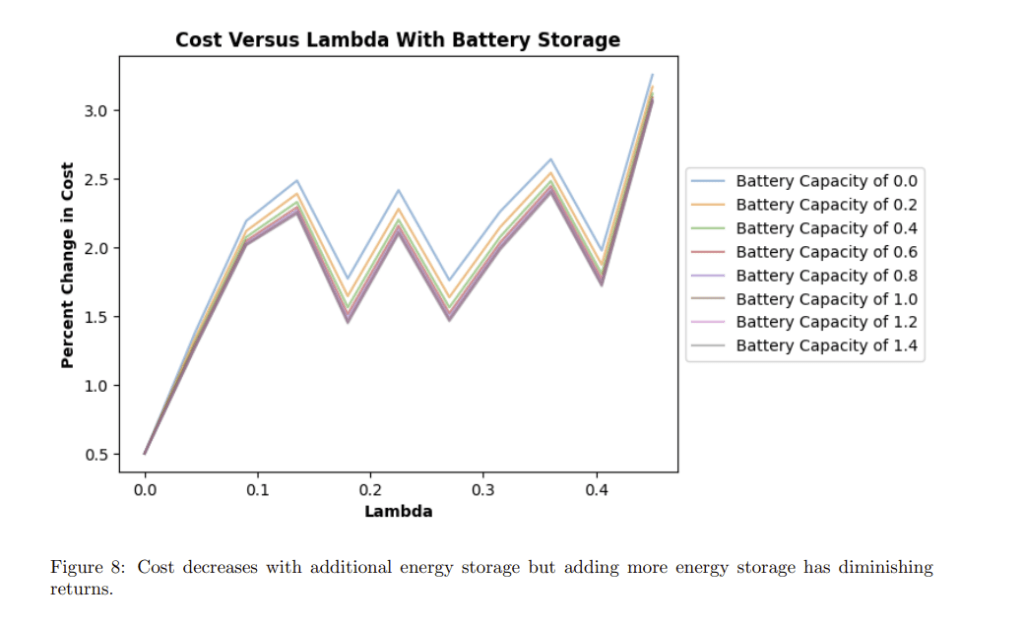

Next, we showed how the cost of electricity improved with energy storage, but this also had diminishing returns. The relationship between the capacity of storage and the resulting reduction in costs can help inform a target price for energy storage.

We finally applied our model to the Princeton microgrid system to determine the feasibility and challenges of transitioning to 100% intermittent, renewable generation. Assuming that our renewable generation will have an capacity factor of 35%, we found that to build a 99% reliable grid system, we would need 116MW of total generation capacity built from twenty-nine 4MW solar and wind farms colocated with 1MWh batteries. The University already has about 16.5MW of solar capacity, but increasing this eight-fold would be a significant challenge given the high land costs in Princeton, New Jersey. The 1MWh of battery storage would also make this endeavour extremely expensive in practice.

Overall, this project was a great learning experience and pushed me to think critically about how grid systems and markets operate at a fine level of detail. Some of the concepts I learned more about included economic dispatch, marginal generators and costs, Gauss-Seidel approximations, and transmission network constraints. Coding these simulations in Python and Numpy using Monte Carlo simulations also pushed my partner and I to think of ways to code more efficiently and make assumptions strategically to decrease our models overall computational complexity, making us better modelers in the process.

If you’re interested in reading our full paper, it is linked below. We would genuinely appreciate any feedback. Thank you!

Paper: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bCG0gy3Z86bt13KSP4sxkNGddfbKN0cf/view?usp=sharing

Code: https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1-IrJ04tBp-PmHltsNsalafOLQqOcZBL_?usp=sharing